The Birth of the Dead

From American Heritage:

The Birth of the Dead

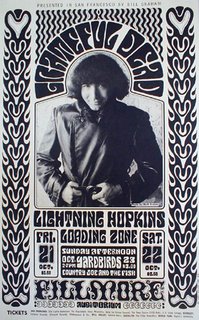

In the coming decades they would play to more people than any performing act in history, but at their first concert the musicians who two weeks earlier had been called the Warlocks had trouble persuading the promoter even to put their new name on the bill. Bill Graham had invited them to play December 10, 1965, at the Fillmore auditorium in San Francisco, but their new name “gave him the creeps.” The group begged and placated, and finally Graham relented. The new name went on the posters, with “formerly the Warlocks” in place of a group photo. So it was that, exactly 40 years ago today, the newly dubbed Grateful Dead played the first of more than 3,000 concerts.

Their original incarnation was as Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, formed in San Francisco in 1963 by the banjoist Jerry Garcia, guitarist Bob Weir, and keyboardist and harmonica player Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. They “played anyplace that would hire a jug band,” Garcia said, “which was almost no place, and that’s the whole reason we finally got into electric stuff.” Adding a bassist, Phil Lesh, and a drummer, Bill Kreutzmann, they became the Warlocks. A new sound came with the new name, as Garcia recalled: “The minute we get electric instruments it’s a rock & roll band.”

Meanwhile the author Ken Kesey started building their fan base. In 1959, as a Stanford graduate student in need of extra cash, he had signed up to ingest hallucinogens in an experiment at the Veterans Hospital in nearby Menlo Park. While he wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, in the early sixties, he continued the experiments independently, joined by a growing number of friends. The group became the Merry Pranksters, and their La Honda, California, commune and drug-fueled public displays formed the model for sixties counterculture. On November 27, 1965, they threw the first acid test, an all-night house party with light shows, tape-loop sound effects, and plenty of LSD, which had not yet been outlawed. The Warlocks, who first met Kesey through a friend of Lesh’s, attended, and as Lesh later wrote, ”It ended up being just like every other acid party—people getting high and doing pretty much what they wanted. . . . The energy was too spread out. It seemed as though some kind of focus was needed to transform diffuse individual energies into coherent collectives. Clearly, music was the answer.”

So when partygoers conducted their experiments at the next acid test, on December 4, the group provided the soundtrack. They became Kesey’s house band, and the Pranksters, the original hippies, now became the original Deadheads. The acid tests formed the blueprint for all future Dead shows. The line between performer and audience, star and event, swirled like everything seemed to at Kesey’s parties and remained indistinct even as the band morphed into a professional touring act. Free-form improvisation, through which the band glorified the experience of the present moment that was so vivid at the tests, became the Dead’s signature.

A few weeks earlier, Lesh, browsing the racks at a local record store, had found a single by another group called the Warlocks. Never quite satisfied with the name anyway, the group brainstormed for days in search of a new one. Kreutzmann suggested “the Vikings,” Weir “His Own Sweet Advocates,” Garcia “Mythical Ethical Icicle Tricycle.” None stuck until the band pored over Lesh’s reference books one afternoon. While Lesh paged through Bartlett’s, Garcia opened the Funk & Wagnall’s dictionary and poked his finger at a random spot. “Everything else on the page went blank,” he recalled, “diffuse, just sorta oozed away, and there was GRATEFUL DEAD, big black letters edged all around in gold, man, blasting out at me, such a stunning combination.” Lesh remembers “jumping up and down, shouting, ‘That’s it! That’s it!’” Others were not so pleased. Weir found it morbid, and of course Bill Graham thought it creepy enough to put off his Fillmore audience.

Bill Graham was wrong. By 9:30 p.m. on December 10, the ticket line circled the block two abreast. The show, which also featured the Jefferson Airplane (as well as acts destined for less eminence, like the Great Society and the Mystery Trend), was a benefit to raise money for the leftist, avant-garde San Francisco Mime Troupe. The Dead played in a hall decorated at either end with signs bearing the word “Love” in three-foot letters. Owsley Stanley, the chemist who almost single-handedly supplied San Francisco with acid in the mid-1960s, sat in the audience. The Dead “scared me to death,” he said. “Garcia’s guitar terrified me. I had never before heard that much power. That much thought. That much emotion. I thought to myself, ‘These guys could be bigger than the Beatles.’” Rock Scully, the band’s future manager, concurred: “We’d never seen anybody play like that before. Jerry was lifting the roof. Of course, we were slightly stoned.” Scully and his friends weren’t alone. “I’m absolutely sure Jerry was tripping, too,” Scully said. “Every now and then, he’d look down at his guitar and I though he was seeing some kind of monster. He was all surprised. Looking over at his hand down the neck of his guitar like ‘Wait a minute. Where is the end of this thing?’”

The concert raised $6,000 for the mime troupe; more important, it brought the Grateful Dead to its first public audience. In 1966, as the Dead played to increasingly packed houses, the Hollywood record industry caught on to the growing San Francisco music scene. The Dead recorded numerous albums with Warner Bros., but they would never have much success capturing the energy of their live shows on vinyl. Their phobia of formula and suspicion of rigidity and routine made for far-out concerts but translated on records, like their 1967 self-title debut, 1969 Aoxomoxoa, and 1970 Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty as inexpert, if charming, imprecision. Garcia explained it in characteristically self-deprecating terms. “We’re really not that good, I mean star kinda good or big-selling records good.” However, their looseness did not betray a lack of ability. When pushed, as by David Crosby on his first solo album and select Crosby, Stills, and Nash tracks, the Dead revealed themselves to be a tight, note-perfect session band. The music was, at its best, an amalgam of Americana, blending Garcia’s bluegrass background, McKernan’s affinity for Chicago blues, Lesh’s classical training, and their collective love of John Coltrane.

In the seventies, as the hippie scene went out of style, the Dead faded into obscurity. Their nonstop tours, though consistently attended, drew almost no attention from the press; their few studio albums failed to make a ripple on the charts. To critics, their output lacked the dexterity of groups with similar influences, like the blues and bluegrass acolytes Led Zeppelin or the super-competent, jazz-trained Steely Dan, but also eschewed the exciting aggression of the equally messy, elaborately iconoclastic punk movement. They were written off as dinosaurs. Garcia was fine with that. “I feel pretty good about . . . stopping being part of that mainstream and just kinda fallin’ back so that we can continue to relate to our audience in a groovy, intelligent way.”

But while the mainstream ignored them, the Dead continued to pick up new fans. By the late seventies the Deadheads were turning into a phenomenon in their own right, a family of unreconstructed and newly turned-on hippies who followed the band across the country to party at each of its concerts. By the time the Dead scored their first top-ten single, “Touch of Grey,” in 1987, the Deadheads were as much a part of the band’s mystique as was their music. Alone among their contemporaries the Dead carried the torch of the sixties continuously through the next decades.

As other bands and artists broke up, died, feuded, or transformed into slick pop acts, the Dead did what they always had. They played. Garcia’s death from a heart attack on August 9, 1995, meant that the last show of that summer’s tour, at Chicago’s Soldier Field a month before, would be the last ever. It came five months and one day shy of 30 years after the first. In addition to the band’s three decades of music, there’s one more thing Deadheads can be grateful for. They aren’t Mythical Ethical Icicle Tricycleheads.

—Christine Gibson is a former editor at American Heritage magazine.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home