Acoustic freedom

From Mercury News:

Acoustic freedom

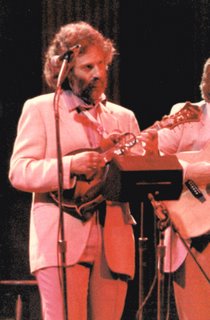

DAVID GRISMAN'S QUINTET TOOK THE STAGE IN 1976, AND STRINGED MUSIC HASN'T BEEN THE SAME SINCE

By Mark Whittington

Mercury News

The revolution began quietly. No shouting. Just two mandolins, a fiddle, a guitar, a double bass. No singing. Then, wild applause.

Music would never be quite the same.

The start of this ``new acoustic revolution'' was Jan. 31, 1976 at the community center in tiny coastal town of Bolinas in Marin County, when the David Grisman Quintet took the stage for the first time. Thirty years later, Grisman continues the revolution with a new version of the quintet, his own record company and as a guest artist, as with the Gypsy Caravan on Sunday in Santa Cruz and Wednesday in San Francisco.

``It was a bunch of visionaries,'' says Grisman, 60, looking back. ``They didn't care about money. They came here to do something different.''

That first quintet featured Grisman and Todd Phillips on mandolins, Tony Rice on guitar, Darol Anger on violin and Joe Carroll on bass. They forged a new form of instrumental music that paid no attention to genres. It freed the fingers -- and souls -- of generations of stringed musicians that followed.

And the audience loved it from the start. The Bolinas hall holds 200, maybe. Some sat cross-legged on the bare floor, others lined the walls. Some folks had brought their kids.

``Sold out, packed,'' Grisman says. ``It was acoustic, without any microphones. It was hardest for the guitar player; Tony Rice would step forward, and we would keep quiet behind him.''

``That audience was absolutely crazy. And I knew they would be,'' Rice says. ``There had never been anything like that. It was absolutely crazy. They couldn't get enough of that.''

``I knew that it was special. That feeling was in the air, maybe it was just in our heads,'' says Phillips, who was playing a mandolin he'd built that he'd strung up for the first time that day. Later in the quintet, he switched back to bass, the instrument he'd learned to play as a child in San Jose. ``From the first song, the crowd just went ape shit.''

In a separate interview, Anger's recollection is identical. ``I don't think it ever occurred to us that people wouldn't go ape shit,'' he says, ``which they did from the very first tune.''

There were a couple more gigs -- a church in Berkeley and a rec center in Mill Valley. Then the quintet toured Japan, even playing a live radio show for 3 million listeners. They returned to record their first record, titled simply ``The David Grisman Quintet.'' It contained such gems as Grisman's ``Opus 57'' and ``Dawg's Rag,'' Rice's ``Swing 51.'' and the Reinhardt-Grappelli classic ``Minor Swing.''

``That record changed everything,'' Phillips recalls. ``I don't know how aware of that we were at the time. I guess later we realized that.''

``I listened to the first David Grisman Quintet record so many times I couldn't even begin to count them. I can't imagine what my music would be like if David hadn't invented Dawg music,'' innovative banjo player Alison Brown, who is on tour in Europe, says by e-mail. ``David and all those great players, Mike Marshall, Darol Anger, Tony Rice and Todd Phillips really opened up the box for those of us who started off in bluegrass music but were interested in getting into other things. Jazz was always kind of intimidating to me as a teenager, but David's music gave me a window through which to peer into the jazz world.''

It broke down the doors and in rushed fine musicians such as Jerry Douglas, Béla Fleck and Edgar Meyer. That flood continues today with the likes of Nickel Creek, Yonder Mountain String Band, String Cheese Incident and the Waybacks.

``You can use your imagination from what came after that music,'' Rice says. ``You could start a tree of offshoots that have come out of that music. It would be a huge tree.'' ``We're seeing all this hybrid music,'' says Anger, who's broken down a few more doors with Psychograss, Turtle Island String Quartet and Fiddlers 4. ``People don't accept any limitations any more.''

``It was something that was waiting to happen,'' Grisman says. ``The instrumental virtuosity side of bluegrass had grown to a place that it could handle it's own thing. But it had to go outside of bluegrass to do that. Once it did that, there were people from outside of bluegrass who got interested. They found a place to do something different.''

The quintet, affectionately known as DGQ, became an incubator for the new music. Even when the original members moved on to blaze their own trails, they were replaced by innovators such as Mike Marshall, Mark O'Connor, Rob Wasserman, Joe Craven, Svend Asmussen, Bill Amatneek, Dimitri Vandellos, Andy Statman. Grisman's musical family also adopted plenty of already famous musicians, such as Stephane Grappelli, Jerry Garcia, Vassar Clements, Jethro Burns, Norton Buffalo and even the Kronos Quartet.

``I've had great musicians come in and out,'' says Grisman, who's appearing as a guest artist at the Gypsy Caravan shows in Santa Cruz and San Francisco.

For him, it's all ``dawg music'' -- ``Dawg'' was Garcia's nickname for Grisman.

``I've always felt that what I do is my personal music,'' Grisman says. ``I didn't want people to show up expecting to hear bluegrass. I was trying to distance myself from bluegrass. I have a high regard for styles, particularly bluegrass. It's about 50 percent vocal, and it's got to have a 5-string banjo played in that (Earl) Scruggs style. We'd eliminated about 60-75 percent right off the top.

``I figured if it had a name, I wouldn't have to keep explaining it. Whatever I do, it's `dawg music.' It's instrumental acoustic music with varying influences -- bluegrass, gypsy, swing, funk . . . '' His voice trails off before he completes the list of influences. Latin, klezmer, pop, jazz. You name it, the self-confessed ``music junkie'' listens to it and it finds its way into his music.

As with all musical success stories, ``overnight'' wasn't quite.

Over the phone from his Petaluma home, Grisman traced the history of his quintet.

``I never really planned to have a career at having my own band. John Hartford was the first guy who told me that I would do that. I wasn't something that I thought was in the realm of possibility,'' he says. ``Nobody in bluegrass wrote instrumentals and had an act that did them. It just wasn't done. I played in bluegrass bands and probably played one instrumental a night.''

But Grisman always wrote instrumentals.

``Bill Monroe wrote tunes. Frank Wakefield wrote tunes. They were my heroes,'' he says. ``I wasn't trying to force myself to write tunes. I just had a list of tunes. Tune in B-flat. Tune in A. I didn't even have names for them.''

Even back at New York University, Grisman would play these tunes with his friend, Artie Rose. Banjo player Bill Keith worked up some of Grisman's tunes, including the now classic ``Opus 57,'' which showed up on the ``Muleskinner'' album.

Grisman traces the roots of his quintet to a 1974 visit by fiddler Richard Greene, who was playing a gig with jazz singer Anita O'Day and staying at Grisman's home in Mill Valley. Grisman's memory is appropriately hazy about details. ``One of us got a call for a gig, hired the other and hired a singer for a gig at McCabe's. Then I got a gig at Great American Music Hall playing opposite Vassar Clements. We said, `Maybe we should do this instrumental.' ''

Clements was being backed by a group of kids called Skunk Cabbage. After a live radio show promoting the show, the members of Skunk Cabbage told Grisman and Greene, ``You know, Vassar belongs with you.'' Those San Francisco shows became legendary.

``I consider those shows the birth of `dawg music.' Jerry Garcia was in there one night, Taj Mahal played bass one night. It was kind of a happening,'' Grisman says. ``We called the band the Great American Fiddle Band. It was kind of exhilarating.''

Anger, who was attending UC-Santa Cruz and playing bluegrass in a Milpitas pizza parlor, was at those shows. ``It was the closest thing to a religious conversion that I have ever had,'' he says. ``They had this symphonic approach, sort of Beatlesque with jazz influences. It was so far beyond any string band music at the time.''

The band became the Great American Music Band and toured as the opening act for Maria Muldaur. ``As soon as I had a vehicle for these tunes, they started pouring out. You couldn't just play hoedowns for 60 minutes,'' Grisman says. ``We were adding some Django Reinhardt and Duke Ellington.''

Then Greene joined Loggins and Messina.

``I was left with some tunes and a concept,'' Grisman says. But no band.

Grisman was playing duets with one of his students -- Phillips, who was trading him mandolin bridges for lessons. ``I liked the way two mandolins sounded in harmony,'' Grisman says of the sound that was at the core of the early quintet.

``We never even talked about that we were going to be a band,'' says Phillips, who envisioned a cross-country quest to learn from all his mandolin heroes. ``David was the first person I went to see and that was the end of my trip. I got to play with everyone right there in his living room. The immersion was so deep, so fast. Suddenly, I was dogpaddling on mandolin.''

Phillips brought in Anger from the South Bay bluegrass-pizza parlor scene. Grisman brought in Carroll, who'd played with the Great American Music Band.

``Pretty soon I had a mandolin player, a bass player and a fiddle player showing up on my back porch to rehearse,'' he says.

That left one missing piece.

Grisman flew to Washington, D.C., to record with banjo player Keith. Rice was playing guitar on the record. They knew about each other but had never met. Rice heard a tape of Grisman's tunes playing in the background after an all-night session. ``I'd give my left nut to play that music,'' Rice told Grisman.

``I heard this music. And I thought, `This is it,' '' Rice says. ``This is a sound that I had in my head and that I had in my DNA for a hundred of years.''

Rice was already a flatpicking legend. He was playing with J.D. Crowe and the New South, a band that included Ricky Skaggs and Jerry Douglas and that remains a touchstone for today's bluegrass bands.

``They were playing in the Holiday Inn in Lexington, Ky., and he made me change my plane ticket and hang out with them,'' Grisman says. ``There were maybe 12 people there. It was kind of depressing seeing this great band with nobody there.''

But during the day, Rice and Grisman would play the mandolinist's tunes. Rice recalls telling Grisman, ``I just don't have the ability to play this music. He told me, `Man, you're crazy. You can do this.' ''

``He may have been playing in the world's greatest bluegrass band but what he was listening to during the day was the Oscar Peterson Trio,'' Grisman says. ``Basically dawg music was what he was waiting for.''

When Grisman returned to California, Rice would call periodically and ask when the gig was. Finally, Rice stopped in Marin County on the way to Japan for a tour with New South.

``One night at 3 in the morning, the phone rang and it was Tony Rice,'' Grisman says. ``I could tell he'd had a couple under his belt, and he said he'd given J.D. his notice. I didn't ask him to do that.

``They all volunteered.''

It was Rice's commitment that knocked the others out. He uprooted his life, packed everything he owned into his car and drove across country to Marin County.

``I knew it was special enough to leave everything I had in Kentucky,'' says Rice, who has moved back to the South but still belongs to the musicians union in San Jose. ``Not only would I do it again, I would do it precisely the same way. I already had this new music in my blood. The whole process of doing that was innate leap into some other music form. I didn't have a choice.''

The quintet rehearsed six or seven days a week, twice a day for almost a year without playing a gig.

``Rehearsal, rehearsal, rehearsal. By the time we started playing we were clinically insane,'' Anger recalls. ``We were like musical Moonies.''

``A little bit nuts, a little too intense,'' says Phillips, who says he continues to bring that same feeling to every project.

They had to invent a way to talk about this new music. They had to bridge cultural gulfs -- Carroll was a jazz musician who had played in Vegas pit bands;, Rice came from an extremely disciplined bluegrass tradition. Anger and Phillips were from the scruffy West Coast hippie wing of bluegrass. Grisman had a bluegrass background and had played with the Grateful Dead on ``American Beauty'' and in bands like Earth Opera and Old & In the Way.

``Each of us had to find a role to play,'' Phillips says. ``That's what evolved out of the hours and hours of hard work. We designed a way to have a five-way conversation. It was a lot of hard work but it all came kind of naturally.''

``Each member had an unmistakable instrumental voice, and every band member had a crucial role,'' says Anger, who admits being a little intimated by Rice's background and by Grisman's cast of guest fiddle players such as Greene, Clements and Grappelli.

They all say they that it was the music they were born to play.

``It was an extremely wide concept of what a string band could be. It was very clear that the group was two or three steps beyond what other people were doing,'' Anger says. ``We were incorporating styles -- pop, classical, bluegrass, swing, more advanced jazz. It was thrown into these dramatic arrangements, and it was completely instrumental. We were using very sophisticated arrangement concepts.

``In bluegrass and string band music, everyone would play all the time. You'd never have everyone drop out so that just one instrument was playing. You wouldn't have an 11-minute song with seven musical sections. You'd never have two parts playing the lead in harmony and two parts playing harmony in serious counterpoint.''

Grisman got discouraged because he didn't know if the music would find an audience, Rice recalls. So he encouraged him: ``I really think we're sitting on a gold mine. There is a sound and a spirit that's coming out of this music that's unbelievable.''

Carroll died in 1983, but other members of the original quintet still are immersed in the genre-bending music. Over 30 years, they have built musical resumes that are pages long. During these interviews, Grisman was rehearsing with European swing musicians for the Gypsy Caravan tour; Phillips was in his Mendocino studio, producing a Hazel Dickens tribute disc; Anger was in an airport, heading to an East Coast gig with his Republic of Strings. Rice, who now longer flies, was driving to a series of shows in the northeast with a quartet that features Peter Rowan.

As always, Grisman is busy, playing music and running his record company, Acoustic Disc. His current current quintet features bassist Jim Kerwin, who's been with the band for 20 years; flutist Matt Eakle, 15 years; guitarist Enrique Coria, 11 years; and drummer, George Marsh, who's back with the band after playing with it for four years in the '80s. The group is recording an album and has a few dates scheduled for the spring.

Grisman looks back with pride at all the doors he's opened.

``I think I've kicked down a whole shitload of them. They were there, and they needed to be opened,'' Grisman says. ``Now, there are some great players who are really taking this thing to a new level. It's very exciting.''

David Grisman with the Gypsy Caravan

Where Rio Theatre, 1205 Soquel Ave., Santa Cruz

When 8 p.m. Sunday

Tickets $30-$36; (831) 423-8209, (831) 421-9200, http://www.ticketleap.com/

Also 8 p.m. Wednesday; Bimbo's 365 Club, 1025 Columbus Ave., San Francisco; $38; (415) 474-0365, http://www.bimbos365club.com/

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home