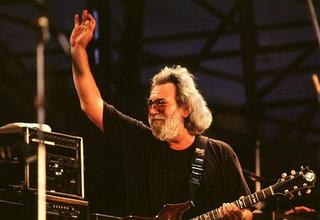

Jerry Garcia: Has It Really Been Ten Years?

From Ear Evolution:

Jerry Garcia: Has It Really Been Ten Years?

A Look Back on Jerry Garcia the Musician

by Jim McCoy

All Photos by Susan McMillman.

I wish there was a song to sing to get you back/But you can't get here from nowhere I guess-Ryan AdamsThe mellow sound of a fingerpicked acoustic guitar exits from the speakers, over which a voice sings of picking up a guitar and improvising a melody not simply for its own sake, but for the cold comfort that is provided as the artist thinks about an unnamed person and an ambiguous "Rosebud." Upon a casual listen, the lyrics could easily be interpreted as a forlorn cry to a distant love, a love long passed and faded in the mind and heart of its subject. The jilted lover responds by crafting a ballad that is complimented expertly by haunting steel guitar lines that fade in and around the track.

Deadheads immediately knew that this track appearing on the second disc of Ryan Adams' Cold Roses (Lost Highway, 2005) was not crafted about a love lost, but music lost; the principal subject of the ballad was not a woman, but an inanimate object- specifically, a guitar crafted in 1990 by California luthier Doug Irwin for Jerry Garcia. The guitar - dubbed 'Rosebud' after an inlay of a female skeleton carrying an un-bloomed rose and flashing an ossified peace sign that appeared on the guitar's ebony cover plate - served as Garcia's primary stage instrument upon its completion. (Although it was eventually cast aside in favor of the Stephen Cripe-constructed Lightning Bolt during August 1993, it was Rosebud that was played at the last Grateful Dead show at Chicago's Soldier Field on July 9, 1995.)Music lovers and musicians alike are often puzzled by the apotheosis of Garcia by his legion of fans. His guitar playing is neither flashy nor particularly speedy; he often dismissed the use of distortion, a rock staple for guitar players since the Sixties; and, his untrained voice did not possess the qualities typically associated with the rock frontmen regularly strutting their stuff in cavernous basketball arenas during Garcia's time. Nevertheless, Garcia himself was able to sell out these very same venues - sans his Grateful Dead bandmates - beginning in the late 1980’s.So exactly what is it, then, that marks Garcia as a rock 'n roll icon? It would be too simplistic - and ignorant - to dismiss his popularity as a result of the drug-induced delusions of a bunch of relics from the Summer of Love era. After all, how many relics (and curious onlookers) are there such that the Grateful Dead were able to fill 100,000 seat racetracks and 60,000 seat stadiums during summer tours in the Seventies and Nineties, respectively? There was certainly something that others were seeing that went far, far beyond a bunch of hippies engaging in reefer madness as part of an all-out effort to avoid the trappings of a regular life and its attendant responsibilities.There really is no one stock answer to the Garcia question; however, one should be quick to recognize that Garcia himself constituted a tripartite musical order that was one part soulful singer, one part superior songwriter (with lyricist and chum Robert Hunter) and one part uncanny guitar player. It is rare for one person to truly be gifted in but one of these areas- let alone all three. (John Lennon, of course, also immediately comes to mind- which shows Garcia to be in pretty elite company.)For comparison, imagine Bob Dylan - or Ray LaMontagne, to use a more recent example -and augmenting their considerable talents with the additional capability of laying down a remarkable, memorable and precise lead break between verses of one of their most moving ballads. Now imagine further that these lead guitar lines are never played the exactly same way again - occasionally for the worse, usually consistent, and sometimes so creatively and perfectly so as to be sublime - in city upon city, night after night.But the ability to improvise effectively - the most cherished, most sought-after skill among serious musicians - isn't the only facet of Garcia's playing that separates him from others in the rock realm. Garcia also was able to meld an understanding of music theory with his ability to adeptly move his pick and fingers around the instrument. Most rock guitar players - from the Sixties through today - simply chose one blues or pentatonic scale and let it rip over all of a song’s chord changes, playing the same notes scrambled in different patterns throughout the guitar's neck. Garcia, in contrast, often considered each chord or series of chords in a certain progression as a separate and distinct entity, using a combination of different scales and arpeggios to outline the changes in the same way that a jazz musician would approach the instrument. A track like Dark Star from 1969's Live Dead- even with the remarkable contributions from the other musicians- is nonetheless likely reduced to an inconsistent, acid-drenched and pedestrian effort afforded only cult status if not driven by Garcia's modal guitar lines. Instead, his lyrical, creative playing elevates it to an example of transcendental psychedelia that must be heard to be believed.It is not just the foundations of psychedelic music that were shaken by Garcia's approach, for he applied his knowledge to the Dead's more conventional music as well. The compilation Without a Net, culled from multitrack tapes from the Dead's 1989 and 1990 tours before keyboardist Brent Mydland's death, shows that Garcia continued to progress throughout his career rather than lazily drifting off into dinosaur status. Garcia's lead guitar fluidly outlines the chord changes between the verses of Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodeloo, making somewhat tricky rock improvisations seem absolutely effortless. Similarly, Garcia adds some off-the-cuff- yet scintillating - jazzy guitar passages in between guest Branford Marsalis' saxophone lines as Eyes of the World nears its conclusion. Garcia's continued progress is even more remarkable when one considers that Garcia essentially had to relearn the instrument following a diabetic coma that almost killed him in 1986.

Those who are quick to dismiss Garcia as a guitar hero often lack an appreciation as to what truly makes him a special guitar player. Undoubtedly, some people just prefer other sounds - and one cannot be faulted for that. Garcia himself once commented during an interview with Rolling Stone that the Grateful Dead was like licorice - some people enjoy it, while others absolutely hate it. But others who seek to diminish- or even attack- Garcia's contributions to the guitar fail to see what separates him from the rest of the lot. Speed and large amounts of overdrive were the hallmarks of guitar virtuosity during the Eighties and Nineties, neither of which were ever espoused by Garcia. His lead playing was unique - not just because he played with a clean, clear tone and typically rejected distortion, but because he had his own voice on the instrument that was immediately recognizable. The lead break on the studio version Unbroken Chain contained on From the Mars Hotel provides such an example. And for those who are intimately familiar with the work of Grateful Dead associate Bruce Hornsby, was there any doubt that it was JG laying down those (admittedly overdriven) solos on Across the River and Cruise Control?Garcia, of course, is not the only guitar player with sonic trademarks - Clapton, Page, Hendrix, Van Halen and even latter-day blazers like Satriani and Vai all possess tones, phrasing and riffs that make them uniquely identifiable even by those music lovers bordering on tone deafness. But when Garcia was on, it seemed like he always played the right note - yet it would be the note that was often completely unexpected. Witness Garcia's uncanny pedal steel playing on the Crosby, Stills & Nash hit Teach Your Children - especially at the song's conclusion, when Garcia suspends a haunting, high-pitched tone before picking, pedaling and sliding into some outro licks.Binding Garcia's talents together was an air of authenticity that surrounded his work. Part of it came from his roots as a banjo player and his love for bluegrass, but much of it probably came from the man himself. Garcia was blessed with "soul," however un-definable that term may prove to be. It's the reason why Garcia doesn't sound the least bit out of place during a bluegrass foray with the Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band. It doesn't sound like Jerry Garcia playing bluegrass music - it is bluegrass music, and it just so happens to be the lead guitar icon of the Grateful Dead performing it.It is this last point that is lost on the devotees of other jam bands that have proliferated in the wake of the passing of the Grateful Dead. Trey Anastasio is an absolutely fantastic guitar player, but one does not get the impression that he is reaching back into the very core of American music as he plays, serving as a medium as he projects the ghosts of musical days gone by into the audience.

Certainly, no individual musician can be faulted for this. Garcia is unique precisely because his music possesses a quality which proves elusive to 99% of the people that ever pick up their instrument.Despite all the rightful praise that can be pushed Garcia's way, it would be naïve- and completely erroneous- to suggest that he constantly approached perfection as a musician. Garcia was fully human, and various CDs, downloads and good ol' fashioned tapes reveal that he would occasionally miss a note or phrase here and there on even his most brilliant nights. (The end of one of his several spectacular solos on the version of Desolation Row on the Downhill From Here DVD provides such an example- with the camera squarely placed on Garcia's fingers as he briefly stumbles at the end of an otherwise well-played gem.) Ironically, this humanizing aspect to Garcia's playing is what endeared him to many. It really wasn't a robot or a superhuman guitar slinger up there on stage; he was an immense talent, but also like the rest of us in some small way as Garcia made some of the same mistakes that you make riffing in your basement or local watering hole.

Garcia's declining heath and unfortunate addiction to a particularly potent form of heroin took much away from many performances during the last few years of his life. Jerry became too human right before the eyes of many Deadheads. Garcia's fingers sometimes struggled and fumbled their way around the guitar neck, and more intricate passages such as the diminished arpeggios in Slipknot! became a painful- even tragic- listen at times. The studio brilliance that appeared on Unbroken Chain decades earlier did not surface on the live versions of the song when it finally debuted in 1995; Garcia, despite his guitar abilities continuing to progress through the first few tours of the Nineties, was unable (or simply unwilling) to outline the chord changes of the jazzy lead break with his formerly adept and inspired playing. On many solos- perhaps due to carpal tunnel syndrome, a loss of sensitivity in his fingertips, malaise, or just plain boredom - Jerry would tend to utilize notes that were a half-step away from his intended targets, thus creating an unintended dissonance where there was formerly a lyrical consonance.There were still moments and shows that were indeed sublime- the version of Visions of Johanna from the 1995 Spectrum run and many shows during October 1994 come to mind- but these moments were certainly fewer and farther between.

These moments, however, are still worth seeking out- to entirely dismiss the years 1993-1995 would deprive a listener of some quality music.Garcia's vocals unfortunately followed the same sad path in the later years. He often mumbled his way through rock numbers that the Dead had been performing regularly for decades. Garcia himself certainly recognized this- anyone who plays at a high level for so long must- but the tapes suggest that Garcia may have tried to compensate by taking the Dead's mournful ballads to new levels with his singing voice as his guitar voice and vocal prowess on other numbers diminished. See So Many Roads- perhaps the lone highlight from the final Grateful Dead performance at Soldier Field- for an example of Garcia crying to the Lord on vocals and mustering what remains of his guitar ability on a night when he otherwise fell flat. Garcia died exactly one month later.

To dwell on Jerry Garcia's shortcomings, however, would certainly be shortsighted. The bulk of his enormous creative output between 1965 and 1995 is original, inspired and provides an shining example of a musician with a unique approach to his craft - and there will likely never be another. Garcia was born of a love of music that is long forgotten in many circles, at a time when LSD experiments were being conducted at Stanford University and a social movement was sweeping San Francisco and the rest of the nation. And above all, he was supremely talented, soulful and authentic. These elements and abilities may never again converge in one place at one time and in one person. If they should, then we will be blessed to have witnessed it. But for now, we should consider ourselves lucky to have on discs, hard drives and cassette tapes what now remains of Garcia's musical legacy.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home