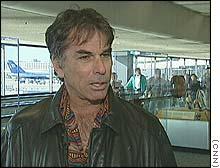

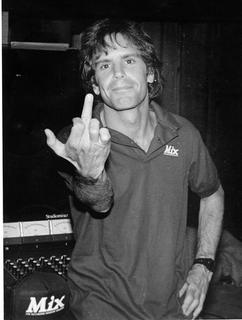

Bobby

From the Monterey Herald:

STILL PLAYING IN THE BAND

For Bob Weir, the music never stops

By RAY HOGAN

The Stamford Advocate

It has been 10 years since Jerry Garcia's death put an end to the Grateful Dead.

For Bob Weir, Garcia's fellow guitarist for more than 30 years, it's hard to think of the past decade in terms of time.

''One moment it seems like yesterday and in another it seems like eons ago,'' he says.

The remaining members of the Grateful Dead have stayed musically active and occasionally team up together (they did last summer as The Dead), but none has shown Weir's dogged determination.

When Garcia died in August 1995, Weir's band Ratdog was starting to take form as a side project that, like the Jerry Garcia Band, would tour when the Dead wasn't on the road. Soon after, it became his focus and took several years and lineup changes to find its shape. In putting together a band, Weir wasn't looking for musicians who knew the Dead's repertoire inside out. Instead, he wanted players who would bring a new approach to his own and the Grateful Dead repertoires, in addition to the songs they would write as Ratdog. Ultimately, he found them.

''I tapped into a well of good musicians who were fun to play with, a lot of whom came from the jazz vein, there's a healthy one in San Francisco,'' he says. ''That made sense to me. I knew I was going to get players with wings. I kept going to that well.''

Ratdog's lineup is Weir, guitarist Mark Karan, saxophonist Kenny Brooks, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, bassist Robin Sylvester and drummer Jay Lane, an original member.

Bruce Hornsby and the Noisemakers play with Ratdog, and aren't strangers to Deadheads. When Grateful Dead keyboardist Brent Mydland died in 1990, Hornsby joined the band to help the transition for new keyboardist Vince Welnick. He stayed until the summer of 1992 and would continue to sit in with the band and its various offshoots.

When asked if he plans to collaborate with his old friend, Weir is emphatic.

''Hell, yeah,'' he says. ''I was going to give him a buzz today and see if he has any notions,'' Weir says. ''I had the notion of just seamlessly flowing from his set to ours, removing one of his guys and putting one of our guys on stage.... the band changes slightly over every few minutes. But that wouldn't give the audience the break it needs, but we might try it once or twice. The situation is rife for borrowing musicians.''

The Grateful Dead redefined the idea of touring for the rock era. Its road warrior mentality spawned an American phenomenon that was the seed for the current boom of jam bands. A common misconception is that the Dead's albums were always afterthoughts to the concerts. With decades to rethink them, several of the studio albums -- particularly ''American Beauty'' and ''Workingman's Dead,'' both from the early 1970s -- are considered classics.

Ratdog has toured consistently for a decade with only 2000's ''Evening Moods'' as its recorded output. Weir realizes the band is overdue for a new disc -- and batch of songs -- but admits a two-year renovation of his Northern California home has kept him out of his home studio, where he normally writes. Unlike the songs on ''Evening Moods,'' many of which were written democratically out of jams and rehearsals, the next batch should bare more of his own ideas. ''My writing facility is such that I might get a fair bit done on my own,'' Weir says.

In concert Ratdog encompasses the span of Weir's career. Set lists include songs from the Grateful Dead, Weir's solo career (''Ace,'' ''Heaven Help the Fool'' and ''Bobby & the Midnites'') and Ratdog originals.

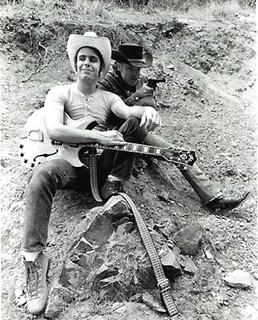

Weir was born Oct. 16, 1947. He began playing with Garcia and Ron ''Pigpen'' McKernan as Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions in 1963. As the jug band switched toward a more psychedelic sound that would incorporate many forms of American music, the group became the Warlocks and eventually the Grateful Dead.

Just as the band was forming its own sound by mixing elements of rock, rhythm and blues, bluegrass and country, Weir took a distinct approach to rhythm guitar. He drew his inspiration from classical composers including Stockhausen and Debussy and jazz pianist McCoy Tyner.

''I wanted to play music and I'm sort of an iconoclast by nature,'' he says. ''I want to squeeze all the music out of that instrument as I can. All that stuff that's been done as rock 'n' roll guitar has been done. It's not my job. I just want to try to expand the horizons a little bit for my own satisfaction.''

Weir's approach made sense in a band that had enough conviction and musical knowledge to mix so many kinds of music into a unique sound.

Popular opinion has marked this year as the 40th anniversary of the Grateful Dead, but to the surprise of Deadheads, the living members of the band are doing nothing to commemorate it. According to Weir, he will play with his former bandmates again sometime down the line.

''The 40th birthday is kind of arbitrary,'' he says. ''It will be my 42nd very shortly, at least playing with Jerry and Pigpen.'' Despite its absence from the stage this summer, the Grateful Dead organization seems omnipresent. Live recordings regularly are released through the ''Dick's Picks'' series and other ventures. The estate of Jerry Garcia also is catching up for lost time by releasing recordings and DVDs of his musical ventures outside of the Dead with the ''Pure Jerry'' series. Festivals including the upcoming Vegoose in Las Vegas are filled with bands presenting the Dead's sense of adventure, community and musical exploration to a generation too young to have witnessed the originators.

For the ''Dick's Picks'' series (which recently released its 35th volume) and archival material released on Rhino records, the band allows others to decide what is put out -- not surprising since the band allowed fans to record their concerts for years, letting people hear performances with peaks and flaws.

''I have veto power but I don't ever expect to use it,'' Weir says. ''I don't have time to do it nor the interest. The benign neglect approach to that is the best one. We'd get too bogged down in the process.''

Living in the moment, particularly on stage, and not getting bogged down is something Weir has done since his teens.

''I live in a dreamlike existence anyway. Time really is relative,'' he says. ''I went up and lived with what we would call Eskimo people in Alaska and kicked around their community. They have all these numerous words for snow and ice and no word for time. I got there and I got 'it.' It's an illusion. I live my life that way, really. I can make plans somehow and get on stage somehow but I don't pay a whole lot of attention to (time).''