Phil's Classmate

O.K. This story really doesn't have that much to do with the Dead. But it's been a slow (Dead) news week and the story is fascinating ...

From Commonground:

The eternal beat goes on

by Mike Myers

From Commonground:

The eternal beat goes on

by Mike Myers

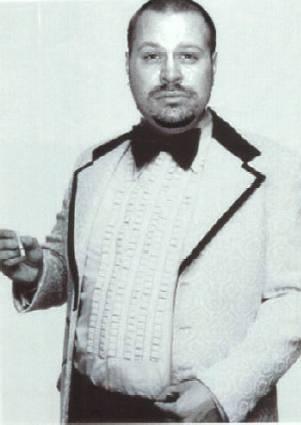

Terry Riley was a barrelhouse piano prodigy by the time he arrived at San Francisco State College in the mid-’50s. Enrolling at the University of California at Berkeley in 1959 and eventually becoming a member of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, an illustrious workshop on Divisadero Street that became a prime gathering place for Northern California’s avant-garde community.

Along with filmmakers, dancers and artists, Riley forged relationships with a list of musicians that now reads like a post-classical/avant-electronic/Eastern-drone who’s-who. Riley exchanged ideas with young composers like Steve Reich and future Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh. Most importantly, Riley encountered La Monte Young at Berkeley. If Riley is the founding father of modern minimalism, Young is the genre’s designated granddad. When the two met in 1960, Young had already developed his ideas on extended tones and how musical time can pass with a minimum of sound. During the ‘60s, Riley, Tony Conrad and The Velvet Underground’s John Cale were part of Young’s Theater of Eternal Music.

The ‘60s were a period of heady discovery for Riley. Outgrowing the honky-tonk piano, he began experimenting with tape manipulations and employed a tape delay device called the time-lag accumulator. Some compositions reflected the use of psychedelics, like the mesmerizing tape-loop construction Mescalin Mix.

“I went to Europe for a couple of years after I got out of Berkeley,” recalls Riley. “That’s when I had a big period of bringing my ideas into focus and got to work with Chet Baker in Paris. I found, through accident, that tape loops build up this long form. I’d sit there listening as this loop was repeating over and over, creating a whole musical form. The way time passes and the way the mind works when it focuses on an object, it’s like a meditation. A tape loop is a kind of mantra.”

All this work however, paled at the debut of Riley’s most memorable composition, In C. A seminal work with its non-stop pulse, repetitive themes and interlocking modal melodies, In C was devised by Riley during a bus trip and written out in the space of two days. In C took Riley’s hypnotic tape-loop concepts and brought the repetitive motif back to traditional acoustic instrumentation. The cosmic sound cycle gradually blossoms into a shimmering aural experience.

Riley is proud of the resilient piece, which has been performed all over the world. There are Canadian and Italian versions, a 25th anniversary concert recording and a rendition by the Shanghai Film Orchestra using traditional Chinese instruments in the ‘70s, and the last Lincoln Center Festival featured an electronic version with Robert Moog playing synthesizer.

All this work however, paled at the debut of Riley’s most memorable composition, In C. A seminal work with its non-stop pulse, repetitive themes and interlocking modal melodies, In C was devised by Riley during a bus trip and written out in the space of two days. In C took Riley’s hypnotic tape-loop concepts and brought the repetitive motif back to traditional acoustic instrumentation. The cosmic sound cycle gradually blossoms into a shimmering aural experience.

Riley is proud of the resilient piece, which has been performed all over the world. There are Canadian and Italian versions, a 25th anniversary concert recording and a rendition by the Shanghai Film Orchestra using traditional Chinese instruments in the ‘70s, and the last Lincoln Center Festival featured an electronic version with Robert Moog playing synthesizer.

When I comment to Kronos leader Harrington that one couldn’t write about Riley without discussing In C, his response is succinct. “It’s the same way you can’t talk about Stravinsky without discussing The Rite of Spring,” he says. “In C is an idea about life, about making music together and about community. It’s so simple and yet so profound, it always sounds right and it always sounds different.”

“In C is a perfect masterpiece,” says Young. “I compare it with the theme from the Funeral March in Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Terry influenced not only Steve Reich, Philip Glass and their protégés but his influence spread out to European rock groups, such as David Allen’s Gong, Can and Tangerine Dream.”

Eager to return to Europe, the Rileys made their way across the US in a Volkswagen bus. “I’d been in Mexico living the hippie lifestyle and ended up in New York broke, so we traded our van for money for a loft,” recalls Riley. Settling in Manhattan, Ann Riley went to work as a schoolteacher while Riley resumed playing music with Young.

Eager to return to Europe, the Rileys made their way across the US in a Volkswagen bus. “I’d been in Mexico living the hippie lifestyle and ended up in New York broke, so we traded our van for money for a loft,” recalls Riley. Settling in Manhattan, Ann Riley went to work as a schoolteacher while Riley resumed playing music with Young.

Riley established himself in Manhattan’s music/art/loft scene. “I wanted to get back to the work I’d been doing after In C,” he says. “I got this little harmonium that had a vacuum-cleaner motor. It was primitive, but I started playing keyboard studies on it and doing some of the first loft concerts around New York.” Riley’s hyperbolic performances in 1967 and 1968 would often last all night and into the morning predating the tranced-out rave culture by two decades.

Tony Conrad was particularly impressed with Riley’s artistic metamorphosis during this time. “Terry’s keyboard work had evolved a conceptual coherence and technical mastery that was on a tier above any musician then playing and was as original and articulate as Charlie Parker in the early’40s or David Tudor and John Cage in the ‘50s,” says Conrad. “The magic and power of the soundscape that Terry created in concerts defied all explanation or understanding. His proficiency as a performer, combined with the intricacy of his rhythmic and melodic structure, left most listeners dumbfounded, simply able to drink in the endlessly undulating liquidity of his sound.”

Besides furthering the technical aspects of electronic music, Riley was also effecting a ground-zero change in the realm of ambient philosophy. West Coast intellectual/inventor/entrepreneur Stuart Brand says, “Riley had profound and immediate influence on Brian Eno, evident in his albums Our Life in the Bush of Ghosts and Music for Airports. In C persuaded Brian that endlessly original algorithmic music doing permutations on a sound palette designed by the composer could make for brilliant listening.

While Riley was recording Rainbow in Curved Air, he also worked with John Cale on the enigmatic collaboration Church of Anthrax. Extending the disciplines they had practised with Young and employing rock drummers who insisted on playing in 4/4 time, Cale and Riley created a cryptic rock/jazz/synth/drone hybrid. “I was recording Church of Anthrax with John in the afternoon, and then I’d go in late at night to record Rainbow in Curved Air,” says Riley. “Essentially, John and I just improvised. One thing we share in common is not too much preparation beforehand.” With critical success, invitations to record with rock artists and the immediate influence of In C, Riley was poised to cement his position in New York’s competitive music community. But it was not to be.

Tony Conrad was particularly impressed with Riley’s artistic metamorphosis during this time. “Terry’s keyboard work had evolved a conceptual coherence and technical mastery that was on a tier above any musician then playing and was as original and articulate as Charlie Parker in the early’40s or David Tudor and John Cage in the ‘50s,” says Conrad. “The magic and power of the soundscape that Terry created in concerts defied all explanation or understanding. His proficiency as a performer, combined with the intricacy of his rhythmic and melodic structure, left most listeners dumbfounded, simply able to drink in the endlessly undulating liquidity of his sound.”

Besides furthering the technical aspects of electronic music, Riley was also effecting a ground-zero change in the realm of ambient philosophy. West Coast intellectual/inventor/entrepreneur Stuart Brand says, “Riley had profound and immediate influence on Brian Eno, evident in his albums Our Life in the Bush of Ghosts and Music for Airports. In C persuaded Brian that endlessly original algorithmic music doing permutations on a sound palette designed by the composer could make for brilliant listening.

While Riley was recording Rainbow in Curved Air, he also worked with John Cale on the enigmatic collaboration Church of Anthrax. Extending the disciplines they had practised with Young and employing rock drummers who insisted on playing in 4/4 time, Cale and Riley created a cryptic rock/jazz/synth/drone hybrid. “I was recording Church of Anthrax with John in the afternoon, and then I’d go in late at night to record Rainbow in Curved Air,” says Riley. “Essentially, John and I just improvised. One thing we share in common is not too much preparation beforehand.” With critical success, invitations to record with rock artists and the immediate influence of In C, Riley was poised to cement his position in New York’s competitive music community. But it was not to be.

Once again, Young influenced Riley when he introduced him to raga singer Pandit Pran Nath. In 1970, Riley went to India to study with Pran Nath. After six months of intense musical training, the singer told Riley he should return to work in America. “It’s a very personal relationship when you study under your masters,” emphasizes Riley. “You don’t come for a lesson once a week-you work very closely because it’s a responsibility on both persons’ part. You have to devote your life to it.” Riley’s mentor eventually moved to the Bay Area, and their friendship lasted until Pran Nath’s death in 1996.

Returning to California in 1971 and taking an instructor’s position at Mills College in Oakland, Riley practised the teachings of Pran Nath and improvised music without notating his work in written fashion. In 1979, Riley encountered the Kronos Quartet at Mills College. At last count, Riley has composed 12 string pieces for Kronos. The quartet’s recording of Cadenza on the Night Plain was selected as one of the 10 best classical albums of 1985 by both Time and Newsweek, and 1989’s Salome Dances for Peace was nominated for a Grammy. On its 1998 10-CD set, 25 Years, Kronos devotes an entire disc to Riley’s work alongside contemporaries like Glass, Reich and Adams.”

Riley has maintained a passion for improvising contemplative solo pieces on the piano. No matter what aspect of music Riley approaches, it reflects the sum total of his experience and integrates a world of sound. Guitarist Henry Kaiser played on the 25th anniversary edition of In C and maintains that Riley is “the most significant and influential composer since World War II”

Yet Riley’s career path has been much more difficult to follow in comparison with those of his contemporaries. While Glass and Reich record for the prestigious Nonesuch label and vie for commissions, grants and concert performances in businesslike fashion, Riley resides at his ranch like a venerable music Buddha, performing sporadically and recording for small record labels such as New Albion and Celestial Harmonies. Although some archival recordings from the early ‘60s have been made available, much of Riley’s outstanding body of work is still waiting to be rediscovered.

Sitting in his secluded home, Riley radiates a distinct sense of inner peace as he looks back at his uncommon career. “The choices I’ve made have been for the music and my own soul,” he concludes. “When I walked away from New York, I knew fame wouldn’t have given me any happiness if it weren’t based on a musical choice. Pran Nath said, ‘Just enough fame to keep doing your work is enough,’ and I thought that was good advice. I feel terrifically lucky every day I get up and give thanks for what’s happened.”

Returning to California in 1971 and taking an instructor’s position at Mills College in Oakland, Riley practised the teachings of Pran Nath and improvised music without notating his work in written fashion. In 1979, Riley encountered the Kronos Quartet at Mills College. At last count, Riley has composed 12 string pieces for Kronos. The quartet’s recording of Cadenza on the Night Plain was selected as one of the 10 best classical albums of 1985 by both Time and Newsweek, and 1989’s Salome Dances for Peace was nominated for a Grammy. On its 1998 10-CD set, 25 Years, Kronos devotes an entire disc to Riley’s work alongside contemporaries like Glass, Reich and Adams.”

Riley has maintained a passion for improvising contemplative solo pieces on the piano. No matter what aspect of music Riley approaches, it reflects the sum total of his experience and integrates a world of sound. Guitarist Henry Kaiser played on the 25th anniversary edition of In C and maintains that Riley is “the most significant and influential composer since World War II”

Yet Riley’s career path has been much more difficult to follow in comparison with those of his contemporaries. While Glass and Reich record for the prestigious Nonesuch label and vie for commissions, grants and concert performances in businesslike fashion, Riley resides at his ranch like a venerable music Buddha, performing sporadically and recording for small record labels such as New Albion and Celestial Harmonies. Although some archival recordings from the early ‘60s have been made available, much of Riley’s outstanding body of work is still waiting to be rediscovered.

Sitting in his secluded home, Riley radiates a distinct sense of inner peace as he looks back at his uncommon career. “The choices I’ve made have been for the music and my own soul,” he concludes. “When I walked away from New York, I knew fame wouldn’t have given me any happiness if it weren’t based on a musical choice. Pran Nath said, ‘Just enough fame to keep doing your work is enough,’ and I thought that was good advice. I feel terrifically lucky every day I get up and give thanks for what’s happened.”

This story was originally published in a longer form by Magnet Magazine www.magnetmagazine.com. Terry Riley www.terryriley.com and San Francisco beat poet Michael McClure www.mcclure-manzarek.com perform bringing beat into the 21st century  electronics, beat poetry and improvised jazz on January 20, 8 pm, Chan Centre at UBC, Ticketmaster.ca or 604-280-3311, www.mundomundo.com.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home