Where have all the hippies gone?

From the Paly Voice:

Where have all the hippies gone?

By Anjali Albuquerque of Verde Magazine

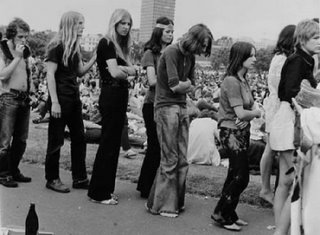

Long-haired Paly students hold "Make Love not War signs"; their pockets conceal suspicious smelling joints. They decided to skip calculus class to watch Jerry Garcia perform. This is Paly in 1968.

Pondering Paly's climate 30 years ago, when hippies, angst-ridden communists, and nirvana crazed Hari Krishna preachers flooded the quad, sparks a strange nostalgia in me. I attempted to understand my obsession with the counterculture and find the remnants of hippie fiasco.

Counterculture residue at Paly now, however, still exists in small doses. Sometimes, I think I've gotten lucky and the guy in the distance with a Pink Floyd shirt is my soul mate, who I've fashioned after iconic counterculture figures; I fantasize he's a Marxist-intrigued intellectual/struggling musician, who blasts The Grateful Dead's Uncle Johns Band in his 1968 VW convertible. But, then I realize I'm horribly mistaken.

Instead, he's the yuppy. While clad in Pink Floyd attire, he's furiously studying calculus and making fun of a "dumb, weirdo" in his cell phone conversation. I'm reminded of counterculture icon and Paly grad Joan Baez's tune "Where Have all the Flowers Gone," which resonates with an eerie truth. I decided to interview Baez, to better understand activism in the anti-war period.

Why I've romanticized the '60s era, I don't quite understand — perhaps an attempt to authenticate myself in a culture where the assembly line spews out millions of identical Abercrombie miniskirts — where conformity unduly reigns the norm, and superficial exchanges propel me deeper into a meaningless void. Or maybe I'm just a lonely teenager in need of something to grasp onto, as a band-aid solution for my truly deeper identity crisis. Whatever the reason, I do, however, realize that my knowledge of the counterculture is at best, superficial. Paly hippies were dropping acid and interacting with the "divine" while protesting against the Vietnam War long before 7-pound Anjali plopped into existence. My desire to negotiate my romanticized counterculture with the real thing propelled me on an adventure back to the '60s, to engage in dialogue with the grown-up flower children.

Joan Baez's fame as a folk singer and activist made her an easy role model for me. At Paly, she was voted the "most radical" in her class and protested against school air-drills, which she believed were silly, as Soviet missiles would immediately annihilate a community. According to Baez, ducking and covering, just wouldn't cut it in the face of nukes. Surprisingly, Baez was somewhat alienated at Paly. She recalls the years, with a nostalgic, yet frustrated tone. "I was considered weird at Paly. This is before the counterculture really took swing in Palo Alto; it was just beginning," Baez says. "But people alienated me. They respected me, but I was on another plane, kind of incapable of being a member of the community — I didn't want to be in a community, where people didn't care about the world around them."

Baez invited an older activist and college student, Ira Sandperl, into her English class to discuss the Vietnam War.

"My teacher was late, and the students just sat there amazed. He was so outspoken, and just blew them away," Baez says. "But as soon as the teacher arrived, Ira was kicked out."

Baez, a striking, poised woman has an instant charm as she recalls her interactions with Bob Dylan, the anti-war community, and Paly students. To encourage dialogue about activism, Baez and her husband started The Center for the Study of Nonviolence in 1969.

"While I'm a folk singer, I would consider my more important role-as an activist," Baez says. "You can't just protest against Vietnam, and think now I'm done. Activism is a lifestyle; music's a channel for the energy."

And things never seemed dull, in this turbulent era. The counterculture energy was focused around music and creative venues. When Ken Kesey and Jerry Garcia desired a caffeine jolt and female interaction in Palo Alto, they flocked to St. Michaels' Alley, Palo Alto's bohemian counterculture hangout.

I sought out St. Michael's Alley naively; 11 dollar omelets and chic sophisticates greeted me, instead of the live music and bearded intellectuals I was expecting. Wake up Anjali, you're smack dab in the middle of expensive Silicon Valley; the bearded intellectuals are now wealthy venture capitalists, get with it! My curiosity toward St Michaels, however, prompted me to find Vernon Gates, the original owner of St. Michael's Alley. He gave me his account of the wacky hipsters.

"They would all come here: The Grateful Dead, Hell's Angels, Ken Kesey. Kesey would nurse a cup of coffee and get all the girls," Gates says. "They were cool guys, very intelligent, very socially aware, not disciplined, rigid like many kids today. There was certain camaraderie with all of us."

The hippie gang's camaraderie was unwavering. According to Gates, when he didn't have a place to stay Kesey invited him to his ranch in La Honda, where Gates subsequently wrote poetry. Unsurprisingly, exposure to live music in this social circle's escapades would coincide with drug experimentation. Altered states of consciousness intrigue me. Sometimes, however, I feel drugs, in the current age, are not used in an intellectual capacity, but rather as a cool pastime.

"Any of those consciousness drugs used back then, was used as a sacrament, as a consciousness raising endeavor, a philosophical inquiry," Gates explains. "It's used to be in a dance, better in a meditative state. Everything falls to a lower common dominator. The bad turns out good."

According to Gates, musicians popularized LSD and marijuana and used them to facilitate creativity.

"We all got turned on. I think LSD was responsible for this. It was a grace wave of Buddha that came down like the wind. We had no choice. Only the creative survived. When you're tripping, you're stripped of rigidity, you're stripped of unnecessary discipline, you realize the most important thing, is channeling creativity."

The Merry Pranksters, which included Ken Kesey and other quirky folk interested in LSD and creativity, embarked on a trip across the country in a psychedelic-painted bus, named Further 1; their goal was to treat Americans to LSD and engage in debate. According to Gates, the Pranksters attended Bay Area concerts and festivals before trekking across the country. The Vernal Festival, a particularly memorable one, attracted 6,000 people. Gates' kaleidoscope eyes spun in a fury, as he recalled the festival.

"We had a firepit blazing inferno. Whales were listening to the music, tripping as well. People had rugs laid out. Even the photographer, a beautiful female running around nude with just a camera on was part of the dance. Hells Angels came down from Oakland, to meet with the Merry Pranksters. It was just as they say, 'dropping out and dropping in.'"

According to Gates, 98 percent of his hippy crowd is currently dead; his nostalgia for the era resonates more sincerely than mine does. I told him, my vision was to start a counterculture. Yet, I was sadly naïve.

"You can't start a counterculture. The moment has to be right," Gates says. "For me, I was going straight ahead, and then I just took a right angle, and it was okay. You'll find your way. I didn't search for anyone. I planted and watered a seed. Then it just grew; people came, the creativity surged." And he's right. I can't help but romanticize an era where students were more socially aware. It seems during the 60s, individuals expressed more indignation towards authority than my peers. Whether manifested through "be-ins," festivals to enjoy existence, or alternative education programs, the flower children demanded change. Sometimes I feel that today's students are too obedient and accepting of teacher's paradigms. The students of yesteryear seemed more concerned with shaping their own education, even though drugs were rampant.

Having read that 'If you remember the '60s you weren't there,' I was curious to what extent psychedelic and consciousness-altering drugs played a part in the counterculture. Were drugs criteria for belonging to an antiestablishment gang, a part of the all-around activist question authority lifestyle, or just plain teenage experimentation?

Apparently, drugs were all of the above, a catalyst for much of the social climate back then. Dan Nitzan, a Paly parent and grad, aided in Palo Alto "be-ins," opportunities to simply enjoy existence with the aid of live music and mind altering substances.

"I remember going to be-ins and realizing hippies are the sweetest people," Nitzan says. "At the El Camino Park be-ins, the Grateful Dead would play. Pitchers of lemonade laced with LSD were near the front stage. This was 1968 before LSD was illegal, so free LSD."

In today's world, it seems there's a perceived dichotomy of "the dumb potheads" and the "enlightened we have better things to do" crowd. To think this dichotomy didn't exist, is pleasantly startling.

"Back then, the culture was pot," Nitzan says. "Lets just say, if you didn't smoke pot, you were suspect!" The government and Palo Alto City Council, not surprisingly, were outraged with the drug-crazed flower children culture. "The thing is when you're stoned and the government tells you something, you think that's B.S. man," Nitzan says. "The government doesn't like drugs because they help people see through the government's deceptions, to actually think for themselves."

The Palo Alto clash between traditional students, families, and their more progressive counterparts created chaos.

An anti-establishment vibe even penetrated middle schools. Mrs. Stewart, a former teacher, was teaching at Jordan Middle School at the time.

"I remember there was a huge conflict, because many students wanted to lower the American flag, which was technically against the law. You have to understand that this was at a time when classes would say allegiance to the flag everyday, so you can imagine what a controversy it caused. According to Stewart, a teacher ended the controversy by lowering the flag himself.

"He was quite a political," Steward said. "I remember him saying 'my son just died in the Vietnam War and this is a tribute to him, and that was it. I'll never forget that. The general atmosphere was just very charged. There were demonstrations at Stanford; people were going crazy."

After an anti-establishment demonstration and a coffee at St. Michaels, counterculture icons Ken Kesey and Jerry Garcia would crawl their way back to Perry Lane, the bohemian center spot for Stanford writers, activists, and musicians. Chloe Scott, a friend of the late Ken Kesey and a member of the Merry Pranksters recounted when Perry Lane was a psychedelic oasis.

"Perry Lane was 24 hours another world," Scott says. "You'd go to Stanford, you'd go to Palo Alto, and then there was Perry Lane, operating apart from it all."

When I told Scott that Kesey's "One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest" is one of my favorite fiction novels of the counterculture era, a wry smile crept over her face.

"Back then, Ken was just another charming, annoying fellow. He had this natural charm," Scott says. "People would follow him, you know. He made chili laced with LSD; we'd all do crazy things. Some people would feel the pulse of trees, sleep in the main oak. Ken was the ring leader."

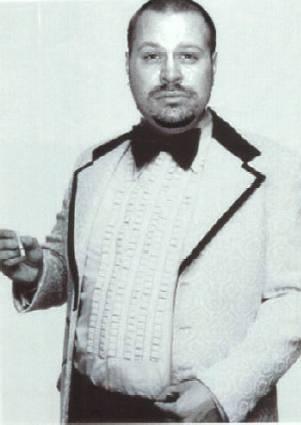

I can't blame many flower children for selling out on their hippie lifestyles. I guess if someone said to me, "trade in your flowers for a suit, and you'll get a job in a booming Silicon Valley company," I would certainly be tempted. Some of the flower children, however, are continuing their activist endeavors. Palo Alto resident Dennis "Galen" Mitrzyk left his job at Hewlett Packard after working there for 19 years, to pursue his life long passions: activism, writing, music, and spirituality.

"I gave up a high paying salary to be a full time activist. But, I have no regrets," Galen says. "We old hippies have to speak up about civil liberties. It's time for freedom to ring out over the land."

Mitrzyk fits my archetype of the adult flower child. He's currently planning for the Satir Satori, a consciousness raising event to occur in the Ben Lomand mountains, which will focus on spiritual enlightenment.

"Society has certainly regressed from the '60s. The government has illegalized a more creative state of consciousness," Mitrzyk says. "This is a deep injustice. This country is ridiculous."

But Mitrzyk still relishes the simple '60s-inspired pleasures. When I visited his house, psychedelic paintings of the "manifesting subconscious" and a medical marijuana "ganja" garden greeted me. It was certainly intriguing. Galen enlightened me with his musical expertise, playing Dylan's "The Times Are a Changin'" on his guitar.

"Dylan was right, the times are a changin', but the good music, the memories, and the people who still really care, will always be around," Mitrzyk says. "That's how we hippies will live on, through those things."

Looking around Mitrzyk's abode, I realized he was right. He was a portal into an into Woodstock, the Merry Pranksters, and activism. Through such exchanges, the spirit of the counterculture stays alive.

"Hippies, hippies. They were the flower children, children in every sense," Nitzan says. "They loved being innocent. Life was just groovy, and for many it still is."

I told Baez about my hope to get an anti-war movement going at Paly. She was ecstatic.

"I was always at the front of the movement, at the cusp. We need a cusp right now. I can't stand being silent," Baez says. "And the machine against us now is so huge, it's time for you guys."

While romanticizing counterculture serves personally more as therapy from a generation that welcomed nonconformists, activism, and political awareness, I hope to bring the culture of the flowers back to our generation. There's a dire need for dialogue and activism. And there is a dire need for a socially aware culture, a culture that this generation can call our own — with musician icons, philosophical inquiry, and even the presence of mind altering substances. Gazing across the street to my future home at Stanford, I'm weary about change, but at the same time I'm anticipating the return of the Palo Alto bohemian. Perhaps, I'll even purchase a school bus, paint it psychedelic colors, and embark on a trip across Bible Belt America — to engage in dialogue with an eclectic group of people. Due to liability issues, the hallucinogens may not be present, but the energy will! You're all invited. Join me for this generation's trip; the magical mystery tour is waiting to take you away!

1 Comments:

Hi - Coincidentally, I just published a post about a house party on the Russian River in 1963 - attended by all the big Palo Alto folkies of the era, including David Nelson and Jerry Garcia. You might enjoy another first person picture of that era. I was a San Francisco kid but had a lot of connections with the Palo Alto folk, having spent my high school years in San Mateo. I think much of what you describe - Perry Lane, St. Michael's Alley, Ken Kesey, and Joanie herself - that's all from the beatnik-folk period. By the time the media discovered the hippies, Joan was already a big star and far from Palo Alto, as I'm sure you know. That's awesome that she gave you an interview. I used to think of her as St. Joan and she was a huge influence on my life in the early Sixties.

Anyway, drop by if you have a chance.

Oh, and by the way LSD was totally illegal in 1968. The law making it an illegal substance was passed somewhere around 1966. Cheers!

Post a Comment

<< Home