A Frank look at the Beat sensibility

From the Boston Globe:

A Frank look at the Beat sensibility

By Mark Feeney, Globe Staff

Tonight at 7, the New England Poetry Club presents its Golden Rose Award to Lawrence Ferlinghetti at Harvard's Yenching Auditorium. Ferlinghetti, bless him, turned 87 last month: proprietor of City Lights Books, in San Francisco; author of ''A Coney Island of the Mind"; and grand old man of that least button-down of literary movements, the Beats.

Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs long ago barreled their way into the canon. They were as much a state of mind as anything else: advance scouts of the '60s, all T-shirts, beards, and Benzedrine, at a time when ties were tied, jaws were shaven, and drugs came out of medicine cabinets.

The most lasting impact of the Beats hasn't, in fact, been on what we read but what we listen to and how we see. Although the music they celebrated was jazz -- both Slim Gaillard and George Shearing make cameo appearances in Kerouac's ''On the Road" -- the Beats' full-bore tempos and pursuit of unmediated experience were rock 'n' roll avant la lettre.

There is, in fact, a distinct Beat-derived stream in rock. Even if Ginsberg had other things in mind when he spoke in ''Howl" of ''the crack/of doom on the hydrogen jukebox," those words surely qualify as one of the first, and most powerfully succinct, definitions of the havoc Elvis and company would wreak.

You can hear a Beat influence whenever Tom Waits sings one of his Skid Row odes. It's there in Patti Smith's visionary diction and hortatory intensity. The Grateful Dead connect to the Beats quite directly, through Neal Cassady, the model for Dean Moriarty in ''On the Road." Cassady lived with the band for a time, and the Dead paid tribute in its song ''The Other One" (''There was Cowboy Neal at the wheel of a bus to Nevereverland"). A Beat sensibility colors the Dead's lyrics (especially those written by Robert Hunter), and it's there in the time-bending exploration and amiable excess of the band's performance ethos.

Above all, there's Bob Dylan. The Beats come to full flower in his language, his trickster-outlaw persona, his wary embrace of American grandeur and weirdness. It makes absolute sense that Ginsberg should appear in the Dylan documentary ''Don't Look Back" and the Dylan-directed feature ''Renaldo and Clara." Dylan's never been Christ, but he had a John the Baptist in Ginsberg.

This fall marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Ginsberg's masterpiece, ''Howl," which with ''On the Road" and Burroughs's ''Naked Lunch" form the holy trinity of Beat texts. That trinity in turn makes up three-fourths of a holy quartet of Beat books. Not to take anything away from the other three, but the movement's true masterpiece consists of pictures not words. It's Robert Frank's ''The Americans."

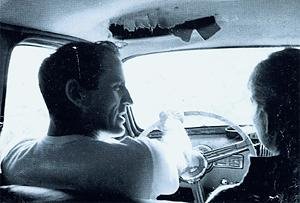

Frank was a Swiss-born photographer who got a Guggenheim grant to spend 1955-56 traveling cross-country to record his adopted homeland. It was a journey both mundane (Frank, who took along his wife and two children in a 1950 Ford, went to the American Automobile Association to plan his route) and exotic (suspicious of his accent, the Arkansas State Police sent Frank's fingerprints to the FBI).

Kerouac, who surely noted the affinity with ''On the Road," provided an introduction to the book's American edition. ''Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand," Kerouac wrote, ''sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world."

It's through Frank's book that the Beats profoundly affected how we see. Frank took the leading tradition of American photography -- the documentary tradition, with its reverence for the particular, the tradition of Mathew Brady, Lewis Hine, Walker Evans -- and doubly enlarged it. He emblematized the particular, making it mythic; and he vastly expanded the accepted view of what constituted vernacular photography.

Evans (who recommended Frank for his Guggenheim) took formal pictures of informal subjects: sharecroppers, tools, subway riders. Frank, good Beat that he was, brought his own informality of approach to bear on informal subjects: flickering television sets, empty highways, (non-hydrogen) jukeboxes.

It's as if Frank took to heart one of Ginsberg's injunctions from ''Howl": ''to converse about America/and Eternity." The book's 83 images are about nothing so much as American immensity, a span of distance both inner and outer. So many of the people pictured in the book stare off elsewhere. Rarely do they look at one another, and almost never into the camera. For all that the book's title suggests otherwise, ''The Americans" is not about people. It's about the space that holds them.

A new anthology of essays on ''Howl" is called ''The Poem That Changed America." With all due respect to Ginsberg, that's a stretch. It's no exaggeration, though, to call ''The Americans" the book that changed photography. What was once a revolutionary document soon became the closest thing the second half of the 20th century had to a manual of photographic style. The Beats have had surprisingly few literary legatees (Ken Kesey, Sam Shepard, Thomas Pynchon in his less paranoid moments), but Frank's photographic offspring are too numerous to list.

''The Americans" might be seen as shadowing the marvelous Stephen Shore retrospective currently at the Worcester Art Museum, ''Biographical Landscapes." Shore, unlike Frank, shoots in color and uses a view camera. But those differences simply underscore how thoroughly, and quickly, Frank came to define the climate of serious American photography. The kinship of sensibility is unmistakable -- a Beat openness and relish of the everyday -- as well as a fascination with space and, of course, the lure of the road.

Perhaps ''The Americans" was most Beat in the now-inexplicable outrage it inspired. A Popular Photography reviewer denounced it as a ''sad poem for sick people." At least that's not patronizing, like Diana Trilling's description in Partisan Review of a Ginsberg poetry reading in 1958. ''I took one look at the crowd and was certain that it would smell bad. But I was mistaken. . . . Certainly, there's nothing dirty about a checked shirt or a lumberjacket and blue jeans; they're standard uniform in the best nursery schools."

Soon enough, they were standard uniform in faculty clubs. The angelheaded hipsters who seemed so subversive are as unmistakably American as the founding Beat, Walt Whitman (Ginsberg took an awful lot from William Blake, too). What once was considered alienation and denunciation we have long since come to recognize as moonstruck love and celebration. In 1956, Frank could have been speaking for the movement as a whole when he pondered his trip. ''I knew I had something," he wrote, ''but I didn't even know I had America." And vice versa.

Mark Feeney can be reached at mfeeney@globe.com.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home